|

| Sir Vladimir's deductions, when diagrammed, make little sense at all. |

In Monty Python and The Holy Grail, Sir Vladimir "tests" the witchness of a peasant woman brought to him by her peasant neighbors.

The claim that she is a witch, though eloquently worked out by Sir Vladimir, is very much flawed. How do we know it is flawed? Well, we "test" the soundness of his argument by using the rules of deductive reasoning: We test the truth of each premise and the validity of the form in which the premises are stated.

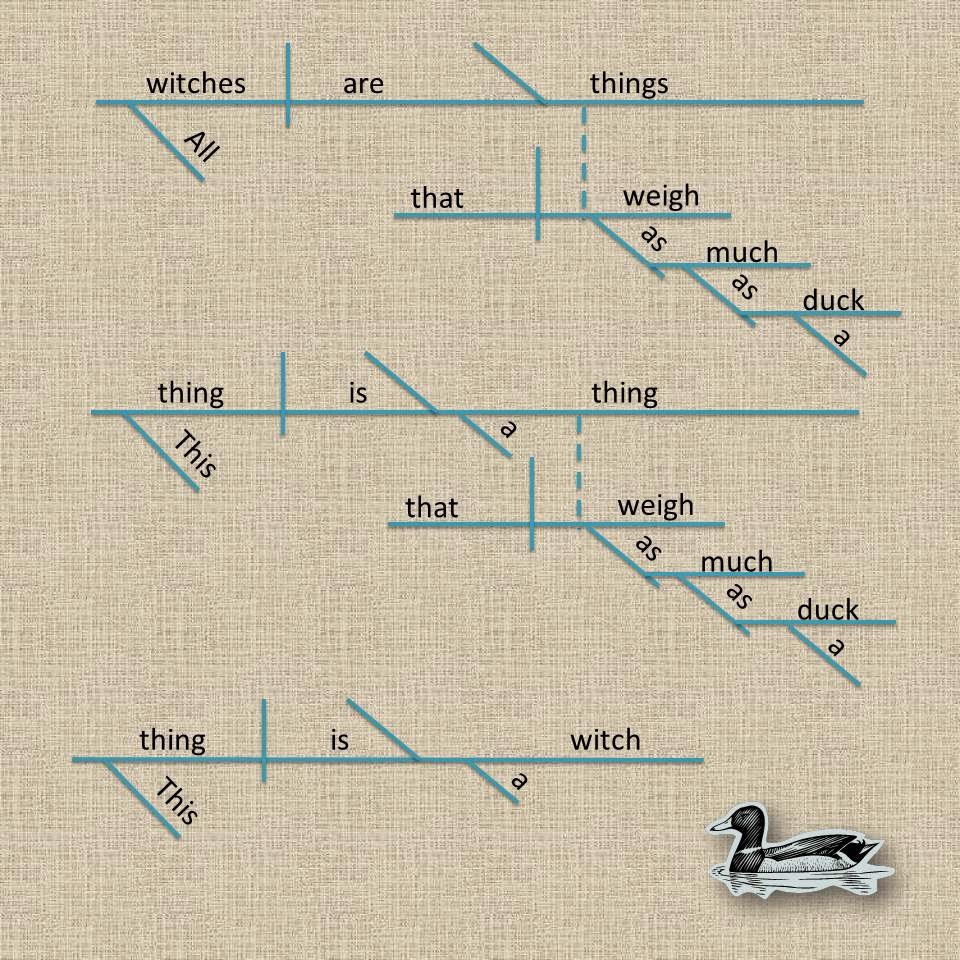

However, even before we run his argument through those two tests of deductive reasoning, we can test his use of language. We can look closely at the structure of Sir Vladimir's sentences by diagramming each of the pieces of his argument, called syllogisms. When diagrammed, we can easily look at the essential elements of each sentence and weed out all of the flowery language that might be obstructing clarity.

Think you aren't up to the challenge of diagramming each syllogism? Well, in the words of The Black Knight, "Come on, ya pansy."

First Syllogism

This syllogism is written in a valid form. The form is as follows:

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are A's.

- Therefore, all C’s are B’s.

The second premise, however, is false: There are things that burn that are not made of wood. Therefore, although the syllogism is valid, it is unsound because it has not passed the test of truth.

- First Premise: All witches are things that can burn.

- Second Premise: All things that can burn are made of wood.

- Conclusion: Therefore, all witches are made of wood.

Does it really take an analysis of form and truth, though, to understand that this particular syllogism is not quite right? Not really. Before ever testing this argument for form or truth, we can diagram the sentences, the propositions, to help us narrow the sentences down to their essential elements. Thus broken down, we can easily determine our A,B,C's and see that the language is vague and ill-stated - never a good sign of a sound argument.

The essential elements on the base lines of these propositions read "witches are things," "things are made," and "witches are made." Someone should probably tell Sir Vladimir that "things" is never a great way to define the terms of our arguments. "Things" is an example of vague language, and in the end, vague language ends up meaning practically nothing.

|

| The Witch's Trial: The First Syllogism |

Second Syllogism

The second syllogism is written in an invalid form. The valid form is as follows:

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are A's.

- Therefore, all C’s are B’s.

However, this invalid syllogism is written as follows:

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are B's.

- Therefore, all C’s are A’s.

Do you see the difference?

Furthermore, it's again quite obvious that the premises are untrue, and even more obviously, the essential elements of these sentences are circular and nonsensical: All three read "Things are things."

Furthermore, it's again quite obvious that the premises are untrue, and even more obviously, the essential elements of these sentences are circular and nonsensical: All three read "Things are things."

- First Premise: All things that are made of wood are things that can float.

- Second Premise: All things that weigh as much as a duck are things that can float.

- Conclusion: So all things that weigh as much as a duck are things that are made of wood.

|

| The Witch's Trial: The Second Syllogism |

Third Syllogism

Just as with the second syllogism, this third syllogism is written in an invalid form. The valid form, as above, is as follows:

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are A's.

- Therefore, all C’s are B’s.

However, this syllogism is written as

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are B's.

- All A's are C's.

Even though slightly less vague than the previous sentences, the sentences in this third syllogism are still quite ridiculous: "witches are made," "things are things," and "witches are things." We also know that the first and second premises are false, which makes this syllogism both untrue and invalid.

- First Premise: All witches are made of wood.

- Second Premise: All things that weigh as much as a duck are things that are made of wood.

- Conclusion: Therefore, all witches are things that weigh as much as a duck.

|

| The Witch's Trial: The Third Syllogism |

Fourth Syllogism

Just as with the second and third syllogisms, this fourth syllogism is, once again, written in an invalid form. The valid form, as above, is as follows:

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are A's.

- Therefore, all C’s are B’s.

However, this syllogism is written as

- All A's are B's.

- All C's are B's.

- All C's are A's.

And, not to be confused with newts or women with carrots tied around their faces, according to Sir Vladimir, "witches are things," "thing is a thing," and "thing is a witch." The first premise is also untrue, making each and every one of these syllogisms unsound arguments.

- First Premise: All witches are things that weigh as much as a duck.

- Second Premise: This thing is a thing that weighs as much as a duck.

- Conclusion: Therefore, this thing is a witch.

|

| The Witch's Trial: The Fourth Syllogism |

How'd you do? Were you able to do it, or did you head off to buy a shrubbery?

Please use the comments box below to let me know if you have any questions, or if you just want to brag that you were able to tackle these syllogisms. I will not say "Ni."

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment